Each year, I run two civic engagement programs at my university. Both programs conclude with mock sessions in which college and high school students take to the floors of the legislative chambers in New York City and Albany, NY. They debate and vote on bills affecting their fellow citizens, following rigorous training modules on public policy making and the legislative process.

It’s heady stuff, to say the least. Young people studying controversial policy debates, and then showcasing their hard work inside the halls of government, while their sitting legislative counterparts watch them do so.

The moment we meet with them for program orientations, participating students demand to know the public policy issue they must ultimately debate in chambers. Indeed, they ask about the issue before they’ve been introduced to the preceding sequences in our training programs—i.e., how legislative bodies function and on whose behalf they engage in the democratic process of decision-making affecting other citizens.

For the last several years, I’ve attempted to match the students’ insistence during that first moment. I’ve responded to their opening question by roaring, “You’re going to debate mandatory prison sentences for people convicted of walking in front of me while sending text messages on their smartphones!”

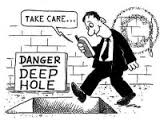

Some take me seriously. A few laugh while I clownishly reenact what I experience on the street every day, weaving and bobbing around people who text on the street. Most of them think I’m silly. Others appear aghast at my policy proposal, along with my promise that I’ll introduce it to their successors next year, once I have my druthers.

A few of them, I would like to believe, are chastened by the idea that text messaging on the street—what I call “strexting” (that term may cloud the point)—can cause real social problems that need to be addressed through public policy.

So, then, what harm is there in “strexting,” anyway? After all, smartphones are “mobile devices.” Is there some form of unmet social obligation when people use the streets and these devices simultaneously?

What I really want to understand is whether smartphone use by pedestrians does a disservice to public space more generally. Do we (yep, I’ve succumbed on more than one occasion!) damage the publicness of shared urban spaces when we aim our heads down and partake in purely private exchanges while using streets and sidewalks?

Fifty years ago, Jane Jacob, Lewis Mumford and a host of urbanists bemoaned the loss of city streets to the automobile. They looked around and saw an incessant run of urban redevelopment programs, which restructured those streets for car traffic and against human scale—away from pedestrian use and community building. While sidewalks grew narrower, the roads adjacent to them rapidly widened in cities across the United States.

The acts of inhabiting and using the city were mutually affected for the worse, signaling precipitous declines in civility, citizenship and, eventually, urban population itself. The suburbs exploded. Cities, on the other hand, diminished as the traditional sites of public interaction and community, not to mention popular negotiation and identity-making. For lovers of cities like Jacobs and Mumford, the times were changing, but not for the better.

By many measures and optics, things have improved since the fall of urban life at the end of the 20th century. Cities have become “hot” again, as millennials and older Americans seeking fuel savings, housing density and urbanity return to the centers from which their parents fled in the post-War period. Even suburbs are transforming and becoming more city-like amidst significant demographic shifts and architectural canons such as the New Urbanism.

The city is in good shape today. So, then, what’s the harm in a little “strexting” now and then? Only a Luddite would resist the growth of “smart” technology in our shared urban spaces. Maybe street texting is merely a novel expression of public space, something that allows us to share city streets with the personal and professional concerns that make cities vibrant and viable in a 21st century economy. In fact, we use our mobile devices to locate the exact places where we assemble in cities. Similarly, we use them to find each other as our cities repopulate. GPS is no joke these days.

There is no denying some of the pro-technology boosterism. The smartphone is here to stay, moreover, that’s for sure. As above, I’ve succumbed; I’ve used my maps apps on the street, not to mention my restaurant finder, the movie locator and others from the convenience of my own palm. I’ve texted friends that I’m running late to meet them, and I’ve certainly gotten caught up in romantic interludes and emotional skirmishes right in the heart of Manhattan’s central business district during rush hour.

Yet, I also find myself concerned that those are the places where a new social problem is currently pooling. Could mobile devices in streets and city spaces usher in a new and ironic anti-urbanist transformation, as the automobile most certainly did a half century ago?

Quite apart from the subtle safety threats posed by thousands of pedestrians rushing around with their heads down and their attentions gripped by what’s going on in the palms of their hands—as opposed to what’s coming right at them—it seems to me that excessive smartphone use in shared urban spaces may produce the privatizing effect once lamented by Jacobs and Mumford as their cities turned hosts to more and cars and fewer people. The car, they feared, would metastasize into a four-wheeled private domicile, one that would segregate citizens from each other and the spaces they had socially contracted to inhabit with each other.

Will the smartphone impact us that way, too? Despite the fact that we mostly use them while moving through pedestrian spaces (don’t get me started on drivers who text!), we appear to be doing so with diminishing regard for the people who share those spaces with us. I can virtually guarantee that when someone is holding me up on the street, seemingly for no reason, he or she is locked into something private, a conversation made of thumb presses. If a cardinal rule of urban life is coexistence and common work, then what should we make of the insularity and failed cooperation that ensues during these moments?

Is urban space less public to the extent that we so often send our heads down and away from each other, toward our “smart” devices?